Historic Environment, Cultural Heritage & Geology

For ACT, this is an area of work we want to expand. The Binsted Arts Festival, a long association with Worthing Archaeological Society, the Binsted Book Group, the Friends of Binsted Church, are all precursors of what we would like to do in the Arun District in the future. Perhaps you would like to volunteer to help with developing this part of our work?

Understanding the environment of the area west and south of Arundel is both about what can be found there today, and also about the wider story. The Maves area is rich in this wider story. It has:

- A geological zone shaped by great movements of the levels of land and sea, worked upon by sea, rivers and streams

- Farming forestry and wildlife arising from varied chalky, clay and peaty soils, the product of natural and human influences

- Medieval relic landscapes from Arundel Forest to a non-nucleated Saxon village landscape to ancient watermeadows

- Features reflecting key changes in English history, from Romano-British to Saxon, Norman and later times

- Landscapes still being shaped today by environmentally sympathetic farming, forestry and community life

Recent researches by Arun Countryside Trust members and independent historians have led to the listing of The Old Rectory Binsted and to the upgrading of the listing of Binsted's church from Grade II to Grade II*. This video explains why the church, threatened by the Arundel Bypass Grey Route, is so special and worthy of protection.

A key partner making new discoveries in this area is Worthing Archaeological Society (WAS) whose members have explored extensively in our area, ever since Con Ainsworth's early excavations at the Binsted pottery and tile kilns at 'All The World'; finding more tile kilns, brickkilns, a Roman villa and other features. The recent Secrets of the High Woods Lidar survey and studies led by the National Park have finally found our elusive Roman Road, alongside other new discoveries. Read more about some of these below.

BINSTED WOODS IN THEIR LANDSCAPE:

NEW HISTORICAL RESEARCH ABOUT BINSTED

Introduction

Arundel Forest contained not just the whole of Binsted Woods but the whole of Binsted village and parish. The Arundel Forest Courts were held at Avisford - the same site as the administrative courts of the Binsted Hundred, which stretched down to the sea. The site of the Court, at Hundred House Copse, was near a point where the Iron Age earthwork (north-south) intersected with the Roman Road (east-west), and where a steep valley gave good conditions for an outdoor meeting place. Two pottery and tile kilns operated very near this meeting place and made lively ware with inset faces. The industry's use of woodland products helped ensure the survival of the woods.

Some of this fascinating history is still visible to the naked eye. The Iron Age earthwork is still visible in the woods, though ploughed out in the fields since Con Ainsworth’s photo of the 1960s. Part of the Roman Road, newly verified by LiDAR, is visible in Barn’s Copse and Brick Kiln Piece. It is also visible further east, where it is alongside the public footpath known as Scotland Lane (the recent report by Historic England confirms that two water-filled ditches and a causeway which form part of it can be seen there.) New historical and archaeological discoveries are being made here all the time...

1. The newly discovered Roman Road in Binsted - "just to the west of Arundel"

The new (2016) report ‘The High Woods from above: National Mapping Programme’, by E. Carpenter, F. Small, K. Truscoe and C. Royall, on www.research.historicengland.org.uk, reveals that the aerial imaging project known as ‘Secrets of the High Woods’, run by the South Downs National Park, has confirmed the route of the long-suspected Roman Road from Chichester to Arundel. This is, as the report says, a discovery of ‘national significance’ (p. 121):

‘More extensive but relatively well-defined sites with a national significance include the fragmented remains of the Chichester to Arundel Roman Road. This is a road that has long been speculated to have existed since the 1940s (Margary) but for which evidence has only been identified during this project. These remains have evidential value but their survival as earthworks allows them to function as a visible link with the past connecting communities with Roman Britain.’

On p.70 the report states that ‘The remains of the road are visible again immediately east of the dual carriageway in Barns Copse. The next appearance is in Brick Kiln Wood immediately east of Binsted Lane. The longest visible stretch of road can be seen as a distinct causeway through Paine’s Wood where at its eastern end its course is picked up by a woodland track [Scotland Lane]. This section of the road has been visited since the survey and found to be a well-defined causeway with standing water visible in the side ditches (James Kenny, pers. comm.).’

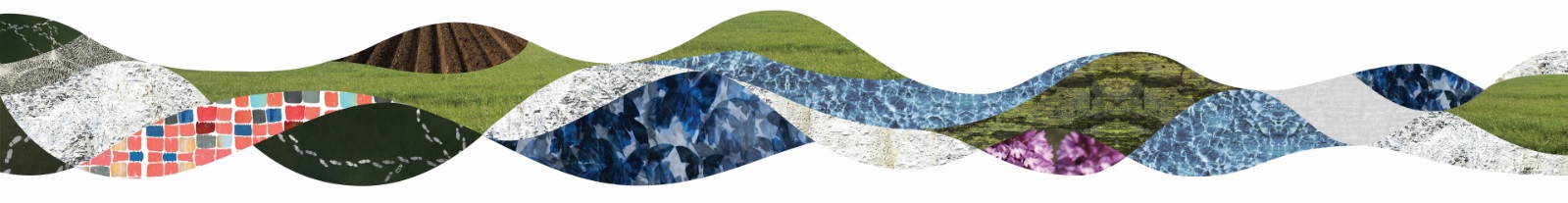

Both the Binsted Option and the Pink-Blue route (old Preferred Route) would cut the line of this road. The main Binsted Option would separate, with a roundabout, the two sections of the road that are visible as earth banks in Barns Copse and Brick Kiln Piece. The ‘alternative alignment’ Binsted Option with a flyover junction at Avisford would separate, with a major two-level junction, the sections of the Roman Road through Fontwell and Slindon from the sections at Binsted Woods. The Pink-Blue route would cut the line of the road near where it can be seen as a ‘well-defined causeway’ near Scotland Lane. Below is the map of the new Roman Road from the Historic England research paper.

The Roman Road from Chichester to Arundel, newly confirmed by LiDAR imaging

The report points out (p. 70) that ‘The identification of this hitherto undiscovered (though speculated) section of Roman Road is of considerable importance, completing another portion of the region’s Roman Road network, it also provides context to contemporary sites including burials found adjacent to the course of the road.’ In Appendix 3 it includes the Roman Road among ‘Sites suggested for further [archaeological] work’ because ‘These roads are highly representative of Roman administration; provide evidence of engineering skills and pattern of conquest and settlement.’

2. Arundel Forest and Binsted’s role in itThe same Historic England report, on p. 88, comments on Arundel Forest (calling it Arundel Chase) that its exact boundaries are not known:

‘The medieval Arundel Chase was an unfenced tract of land within which the Earls of Arundel owned all the deer (though not all the land) and over which they had the right to hunt. The exact bounds of Arundel chase are not known, but it encompassed a vast area that extended from the River Arun almost to the Hampshire border and from the coast to the north side of the South Downs (VCH 1997, 51-52). Chases (more usually called Forests) were reserved for the highest ranks in medieval society with the majority owned by the king (Rackham 1986, 131).

However, more detailed and updated information about Arundel Forest can now be found on the internet site of John Langton and Graham Jones’s project ‘Forests and Chases of England and Wales c. 1000 to c. 1850’, based at first at St John’s College, Oxford, now at the Oxford University Environmental Centre (http://info.sjc.ox.ac.uk/forests/Index.html). The site includes an atlas of the whole of England and Wales, which if you click on the relevant panel brings up a map of the forests in that area.

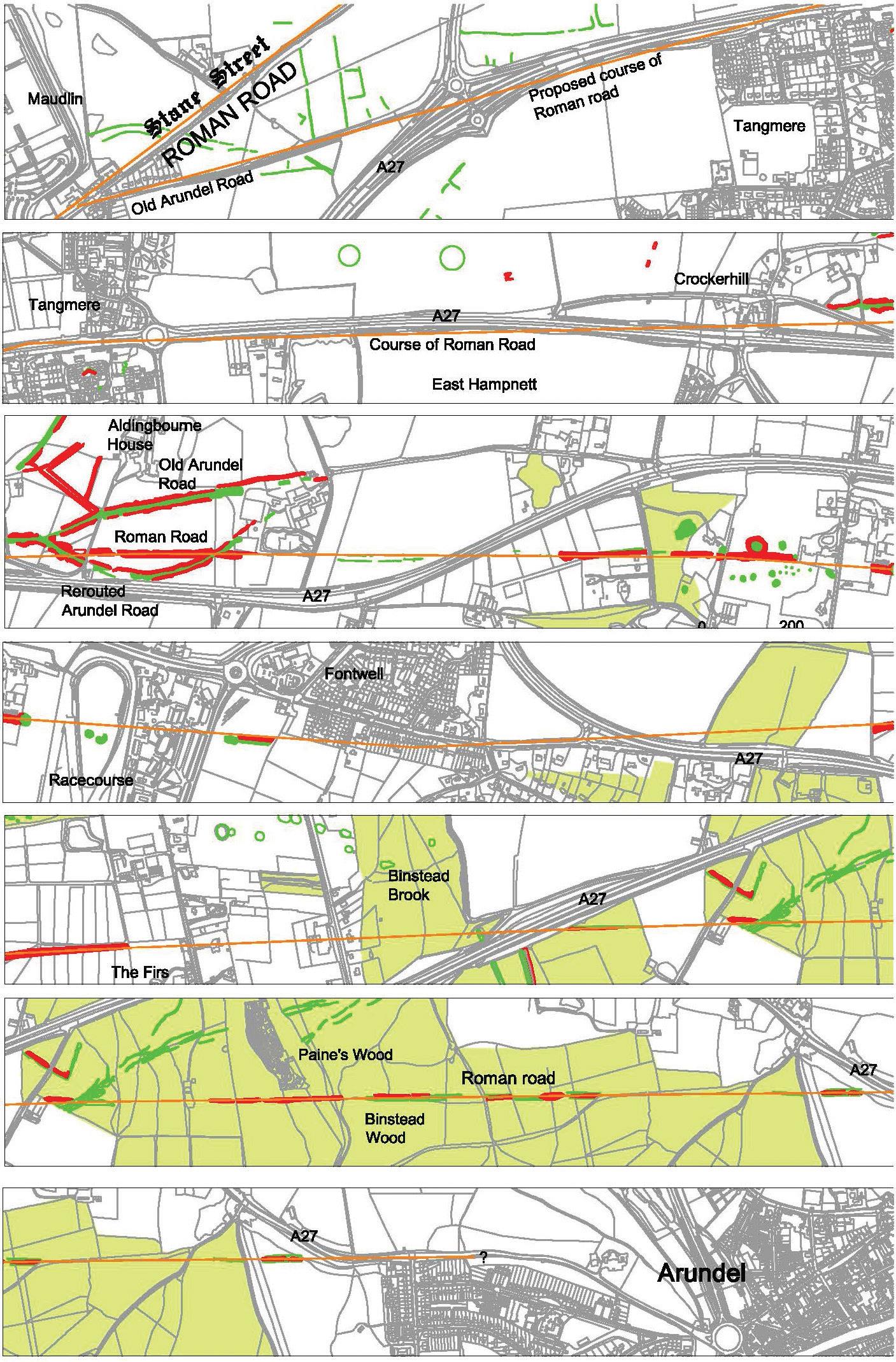

The map of Arundel Forest, showing an older and a newer boundary, has information at the side making it clear that it included Stansted, Broyle, Singleton, Charlton and Houghton forests. It also shows parish outlines; the whole parish of Binsted was included within the older boundary of Arundel Forest (shown by a dotted black line). So was the whole of Tortington Parish, including Tortington Common.

The whole of the Secrets of the High Woods project area is also included in the Forest: this is not a coincidence, since both Arundel Forest, and the SHW project, aimed to include mainly wooded areas on the Downs – for the Forest, because they offered the best hunting and protection for the venison, and the least interference from settlement and agriculture; for the project, because the area offers a rich source of unresearched archaeological remains that have hitherto been hidden in woodland, but can be detected with LiDAR. This map, and whatever I or other researchers may discover about Arundel Forest, are therefore useful as background for the whole SHW project.These boundaries for Arundel Forest are presumably based on research into the lists of place names on the boundary, which are available in ‘Two Fitzalan Surveys’, Sussex Record Society Vol. 67, edited by Marie Clough, 1969. This contains English translations of three late-mediaeval documents known as Books A, B and C. Book B contains two descriptions of the Forest of Arundel.1

Part of the map of Arundel Forest from the site mentioned above, showing two boundaries, an older and a newer, with Binsted and Tortington parishes marked.

1 This is the first one (Clough, p. 92): ‘BOUNDS OF THE FOREST OF ARUNDEL. These are the bounds of Arundel Forest, delimited by 24 of the best men of the district [their names are listed], who say on oath that the forest boundaries go from the Forest of Fysshebourne to Crookerhill and to Codelawe, and to Ryham and Avesford, and thence through the marshes of Tortynton to the Ryver, and following it to Hoghton; thence to Papelsbury and thence to Cranbrugge and thence to Berkhale; thence to Nonemaneslond, and thence through Waltham to Babele, and thence to Hayham of Cockyng and Northmerdon; thence to Compton, where the bounds curve down towards the sea.

And formerly they began at Avesford, and thence to Chesseharghes towards the south; thence to Molecoumbe and thence to Wynkyngg and thence to Suuebeche and thence to Crockerhull.’3. The nature of the Forest: could it include farming and pottery kilns?

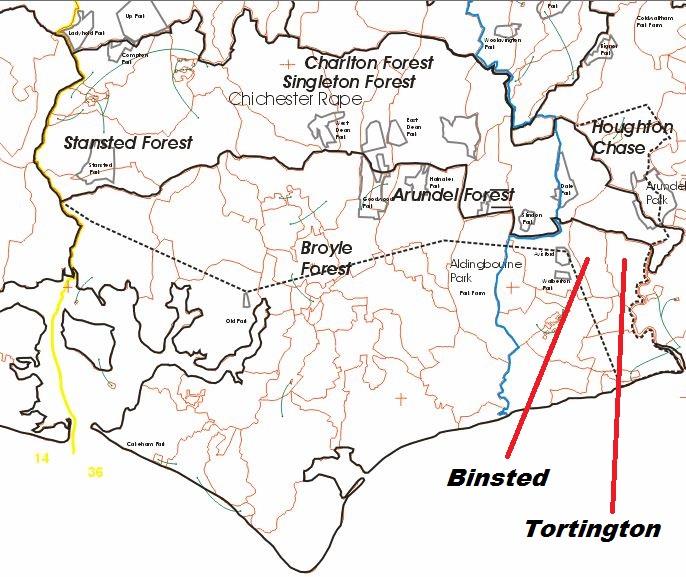

Having found that the whole of Binsted Parish was included in Arundel Forest, contrary to what is suggested in the Victoria County History article on Binsted, I needed to ask what being in the Forest meant, in terms of land use. How does this situation square with the picture given in the VCH Binsted article of a spread-out farming community in mediaeval times, with a central area of arable land, farmed in strips? Also, we know there were two tile kilns in Binsted – dated to the 14th century, or from the late 13th century to the early 15th century. These have both been excavated – one in the 1960s by Con Ainsworth, one in 2003-6 by Worthing Archaeological Society. A copse is called Brickkiln Copse, and another is called Brickkiln Piece, suggesting there were also one or more brick kilns. One of the tile kilns was also a pot kiln, and Binsted Ware is known to historians of mediaeval pottery.

How do these fit into the idea of a forest?

It is straightforward to show that Binsted was farmed in Saxon and mediaeval times. VCH Binsted says‘The Anglo-Saxon name Binsted signifies a place where beans were grown’, so the agricultural image, at least of part of the Parish, probably the central fields, is a correct one. This farming activity does not mean that outside its woodland Binsted was not in Arundel Forest. It seems that if you could pay, you could do almost anything in a forest. The Royal Forests of Mediaeval England, by Charles R. Young (Leicester University Press, 1979), p. 6, gives a good summary.His book is about royal forests, but I assume that by implication the same is true of forests made over to Barons: ‘In addition to the legal and administrative significance of the royal forest, the economic value of those areas was considerable, both for the fees the king could collect by authority of the forest law, and by the economic activities on royal demesne and the lands owned by others with the royal forests. Royal forests produced timber and other forest products by royal licence, but there was also farming, cattle and horse raising, mining, iron-making, and many other economic activities taking place within forest borders.’ On p. 55 he remarks: ‘A rather obvious illustration that economic factors could outweigh hunting in policy decisions is the routine policy for dealing with assarts by assessing fines and collecting rents rather than requiring that assarts be abandoned in the interest of keeping the area undisturbed for the beasts of the forest.’

The image of mediaeval forests is changing: John Everitt, director of the National Forest Company, says of the newly planted National Forest in the Midlands: ‘This is not a closed canopy, wall-to-wall forest, but forest in the mediaeval sense, with a mosaic of habitats, of trees, open grassland, pastures, and communities’.2 This is still what the landscape of Binsted feels like. To rigidly demarcate the National Park woodland, and put a new road through the rest of Binsted, would destroy that feeling of history and connection with the past.

2 Quoted in the Guardian, 7 August 2016, ‘How millions of trees brought a broken landscape back to life’, by John Vidal.

4. The Hundred court at Hundred House Copse

One important piece of evidence about Binsted’s role in the Forest is the existence of a wood within Binsted Woods called Hundred House Copse. Hundreds were administrative units of mediaeval England, and the Hundred in which Binsted lies was originally called Binsted Hundred. The VCH article on Avisford Hundred says that the Hundred was known as Binsted Hundred in 1086, and had its new name, Avisford or Avesford Hundred, by 1166. The change of name happened because the forest court (‘Aves’) also met there.

The Hundred court was presumably an outdoor meeting place, making use of features such as the steep slope of the sides of Binsted Rife valley and the brook in the bottom of the valley – and the ford across it - to make it recognisable, and also making use of the reflective qualities of the valley’s steep sides to make it easier to speak to large numbers of people. These points are from an article ‘Identifying outdoor assembly sites in early medieval England’, by John Baker and Stuart Brookes, in the Journal of Field Archaeology, 2015, vol. 40, no.1, pp. 3-21. They say ‘One category consists of hundred meeting places located at significant points on major routes. Significant points include the intersection of two or more routes or a road and a stream (fords routinely feature in the names of hundreds and their probable meeting places), or a marked change in the direction or incline of a path.’ The LiDAR survey has now shown that the Roman Road passes close by, to the north of Hundred House Copse, so this meeting place was at ‘the intersection of a road and a stream’.Baker and Brookes also state that parish boundaries are often close to such meeting places; the Binsted rife was the Parish boundary up to 1937 when Binsted was joined to Tortington, then Walberton. The meeting place at Hundred House Copse was also near the boundary of the Hundred, which stretched from Binsted down to the sea; it was also near the edge of Arundel Forest. Another still older boundary is close by: the Iron Age earthwork (bank and ditch), which went from Little Tortington Stream in the south of Binsted, and northwards to the top of the Downs, passes through Hundred House copse from south to north. At the top of the Downs it joins the similar earthwork called War Dyke which descends to the Arun. The name War Dyke is currently given to the whole earthwork – the eastern one to the Arun and the north-south one down to Binsted. Baker and Brookes suggest that ‘The reuse of ancient monuments as assembly places might be interpreted as a dialogue with the past, conferring legitimacy and authority to proceedings or oath-taking rituals’. All these factors suggest Hundred House Copse was a very old meeting place which predated the formation of Binsted Parish as an administrative entity.

What did the Hundred courts which met here deal with? A letter to me in 2005 from Heather Warne, author of the VCH article on Binsted, about Arundel Forest, usefully describes this. ‘In the Saxon and mediaeval periods rural administration was carried out in areas, by periodic meetings of all residents. These meetings were called Hundreds and they dealt with matters such as the regulation of weights and measures, the impounding of strays, the apprehension of wrongdoers and the upkeep of the highways. Binsted Hundred, as

mentioned in Domesday, was the Hundred for the Binsted area. It drew in people from Binsted, Barnham, Climping, Eastergate, Felpham, Ford, Middleton on Sea, Tortington, Walberton, Yapton and South Stoke. It is assumed that the area recorded as ‘Hundred House wood’ is the site of the meetings.’The article for VCH on Avisford Hundred usefully gives some more details. ‘The view or court oversaw street nuisances and the maintenance of roads, ditches, streams and fences, pleas of debt, trespass, detinue, and assault were heard between the late 13th and 15th centuries, and in the 16th century cases involving theft, slander, an affray, right to wreck, the use of common pasture e.g. at Rewell in Arundel, and coining’ (VCH, Avisford Hundred article).

How do we know that this meeting place had anything to do with the Forest courts? The link is described by Heather Warne in the same letter to me. She said: ‘Binsted Hundred descended under the name Avisford Hundred, a place name which makes sense if it is derived from aves and ford, meaning ‘at the ford of the aves’. ‘Aves’ is an obsolete word, formerly signifying a particular kind of court which dealt with Forest regulation. That the names Binsted and Avisford are alternatives for the same Hundred strongly implies a wood court connection with the locality…My own interpretation is as follows. Where large forests existed, meetings of people who had common in the forest took place seasonally, at the aves courts. Binsted Hundred (at Hundred House copse), also then known as ‘at the aves ford’, was the venue for such meetings. These people would be the same members of the broad community who had the duty to attend the Hundred court. It would be convenient therefore to deal with both types of business at the same place. Such courts were often held towards the edge of forest areas because at least once a year the business [of the court] was to drive the forest of the outpastured animals and re-allocate them to commoners to take home for the close season – just as they do nowadays on the New Forest.’

It seems likely, then, that meetings both of the Hundred and of the wood courts took place at Hundred House Copse – possibly not then as wooded, at least in the south, as it is now, so that sound could bounce off both sides of the small valley. The importance of the wood courts predominated over the old name for the Hundred when people were referring to it, leading to the name change from Binsted Hundred to Avesford or Avisford Hundred. The small triangular copse at the south end of Hundred House Copse is called ‘All the World Copse’ in the Binsted Tithe Map of 1838. The name may date back to the human activity caused by these local courts. This history, and the enduring names, link the woodland into the rest of the landscape. Such links would be broken by a new road through Binsted.5. The mediaeval tile and pottery kilns in Binsted

Still another activity at Hundred House Copse was the mediaeval tile and pot kiln. Two sites containing mediaeval kilns have now been excavated in Binsted. The first, a combined tile and pottery kiln at SU 978065, is Historic England monument no. 248972. According to their description, it made ‘an extensive range of 13th to early 14th century pottery, including the well-decorated glazed jugs classified as West Sussex Ware. The kiln produced, in addition to normal roof tiles, decorated floor tiles, ridge tiles, chimney pots etc.’ It is now within (and under) the steeply sloping garden of the house called Ashurst. Possibly the site of the house, on a flatter area higher up the slope than the kilns, was near, or even at, the possible Hundred House meeting place. The house and its garden, including the kiln, are within the National Park boundary (the lane called Hedgers Hill being the boundary), and the Lidar area. Another kiln site nearby, from the same period, on the opposite side of Binsted Lane on a flatter site, was excavated by Worthing Archaeological Society in 2005-6.

The notes of archaeologist Con Ainsworth, who excavated the Hundred House Copse kiln site at Binsted in 1963-6, are available on https://walbertonbinsted.wordpress.com/pottery-kilns-tile-kilnsbrick-kilns. The website summarises the information in VCH about Binsted’s pottery industry and also gives Con Ainsworth’s own notes about the excavation. (He did publish a short article about it, ‘A tile and pottery kiln at Binsted, Sussex’, Mediaeval Archaeology vol. XI (1967), pp. 316-17, and Fig. 91.) The website also carries many excellent press photos of the kiln dig. Below is one of them – showing the site of the kiln excavation in relation to the house, then a flat-roofed bungalow, now a substantial house called Ashurst with a B and B business. At the time of Con’s excavation, the house was called Tyghlers, and had only recently changed its name from ‘All the World’.

The notes of archaeologist Con Ainsworth, who excavated the Hundred House Copse kiln site at Binsted in 1963-6, are available on https://walbertonbinsted.wordpress.com/pottery-kilns-tile-kilnsbrick-kilns. The website summarises the information in VCH about Binsted’s pottery industry and also gives Con Ainsworth’s own notes about the excavation. (He did publish a short article about it, ‘A tile and pottery kiln at Binsted, Sussex’, Mediaeval Archaeology vol. XI (1967), pp. 316-17, and Fig. 91.) The website also carries many excellent press photos of the kiln dig. Below is one of them – showing the site of the kiln excavation in relation to the house, then a flat-roofed bungalow, now a substantial house called Ashurst with a B and B business. At the time of Con’s excavation, the house was called Tyghlers, and had only recently changed its name from ‘All the World’.Part of Hundred House Copse can be seen south, west and north of the excavation. The remains of the Iron Age earthwork, known as War Dyke, can also be seen in the fields east of the excavation. Only a small linear hump remains to be seen, but in this photo it is marked clearly by two large trees. The smaller house on the site, in the foreground of the photo, still exists much as in the 1960s. The way Hundred House Copse falls away to the east (left of the photo), into the steep-sided Binsted Rife valley, can also be seen. Woodland in the garden of the house down the slope to Hedgers Hill (just out of the bottom edge of the photo) has now mostly been cleared. Below are two more photos of the excavation.

Below is one of my own photos of the 2005 dig by Worthing Archaeological Society at another kiln site in Binsted, very near the first one. This one is in the field opposite the Black Horse pub (visible in the photo).

Another photo shows more of the structure of the kiln, and the fact that it is entirely built of tile wasters – possibly from the other kiln site nearby.

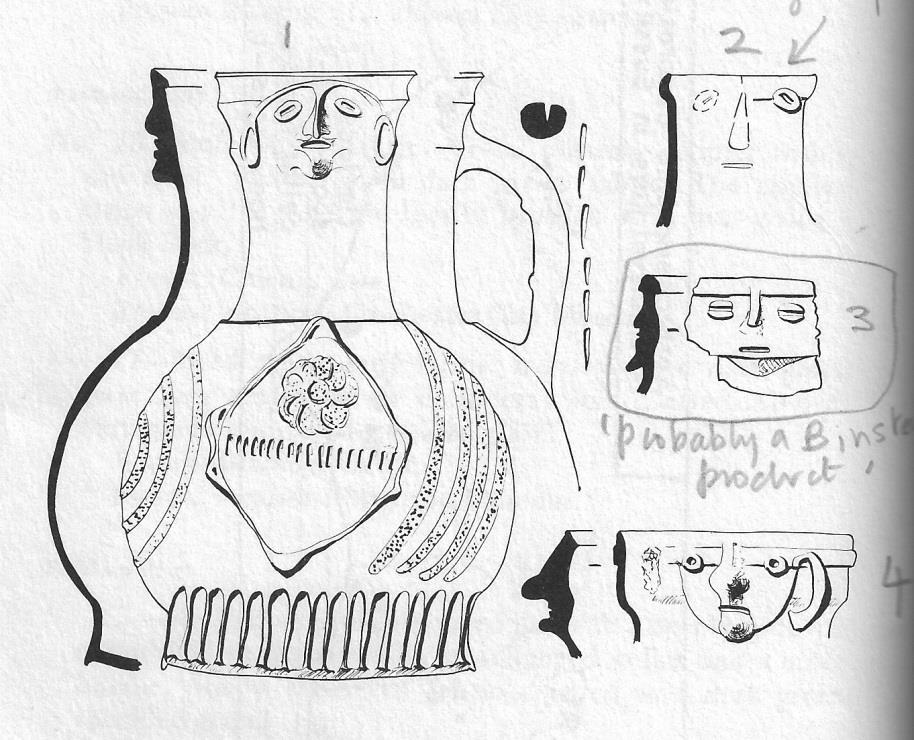

K.J. Barton’s book, Mediaeval Sussex Pottery (Phillimore, 1979), includes more information on Binsted Ware. Jugs with faces, known as anthropomorphic decoration, are frequently mentioned and it would be good to know if any were made at Binsted. Unfortunately the book is confusingly laid out and full of proof-reading errors. I interpret his information here as follows. The illustration on p. 114-15, in the section on anthropomorphic decorations, is supposed to show 12 pieces of pottery to go with the 12 preceding descriptions, but only shows 9. The illustrations of pieces numbered 7, 8 and 9 are missing. Also, the first 5 pieces of pottery shown are not numbered. Careful inspection of the preceding descriptions allows you to number them 1 (the large jug at the top on the left) then 2, 3, 4 and 5 from top to bottom on the right. Thus it is possible to deduce that no. 3 is ‘probably a Binsted product’! It is a ‘standard West Sussex ware face…slightly sandy buff to pink coloured fabric with an apple-green glaze. Roughly built of applied pieces, the eyes are suggested by horizontally-slashed applied pellets, and the mouth is also slashed, there is also a beard…found: Selborne Priory, Hampshire. Present location: The Curtis Museum, Alton, Hants’ (Barton, p. 111). Part of his illustration is below.

The Binsted pottery kilns show a thriving industry, based on the nature of the site, with water, clay, a road, and woods available, also the possibility of water transport down the Rife to the Arun. Without wood nearby for fuel such an industry would not have been possible. Further, the industry ensured the survival of the local woodland. Oliver Rackham points out that ‘the survival of almost any large tract of woodland strongly suggests that there have been industries to protect it against the claims of farmers.’ He also points out that charcoal, used in iron smelting and presumably used also in kilns, ‘came mainly from underwood and was too fragile to transport far’; ‘Fuel-using industries lived near woods because ores and finished products were easier to transport than charcoal’ (Trees and Woodlands in the British Landscape, Revised Edition, 1995, p. 86). The tile and pottery industries at Binsted are part of the explanation of why Binsted Woods have survived millennia of removal of woodland for agriculture and building.

6. Concerns regarding the future of Binsted Woods in their landscape

Most obviously, the archaeological remains in Binsted – Iron Age earthwork, Roman Road, mediaeval tile kilns - may be physically in danger from the Binsted route option for the Arundel Bypass being considered by Highways England. The meaning of these features in terms of their landscape and community-continuity context would also be altered and obscured by that route.

Another important danger is that the link between the woods and their surrounding landscape would be lost. The road route through Binsted, theoretically ‘avoiding’ the woods, would sever them from their context. Instead of being part of a whole landscape, in which they played an important role, providing fuel for the pottery and tile industry as well as shelter for the lord’s deer and food for the farmers’ animals, they would be left as meaningless fragments of woodland for drivers to look at as they passed by.

The historic landscape environment of Binsted requires conserving as an integrated, unsevered whole of woods, fields and village.

Emma Tristram, 2016.

Some of this research also appeared in her 2016 contribution to the Secrets of the High Woods project.