Last week I had the pleasure of helping a colleague monitor his dormouse boxes in a private woodland within the Mid Arun Valley woodland complex. We parked along Binsted Lane and followed the field hedgerows to the woods. The hedges were just coming into life – explosions of clustered white Blackthorn flowers, yellow willow catkins smothered in honeybees and the vivid fresh green of new leaves bursting from the buds of hawthorn, elder, spindle, hazel, oak and more. Birds flitted hither and thither – darting in and out of the living corridor – robins, wrens, chaffinches, chiff chaffs and others. Skylarks, in the adjacent fields, soared skywards singing as we walked past. Ian, ever sharp-eyed, spotted a lizard basking in the sunshine on a small patch of bare earth on the hedge-bank next to a clump of primroses. It darted away as we approached. Also basking on the hedge-bank was a tatty looking peacock butterfly – presumably one of last years’ having over-wintered.

Last week I had the pleasure of helping a colleague monitor his dormouse boxes in a private woodland within the Mid Arun Valley woodland complex. We parked along Binsted Lane and followed the field hedgerows to the woods. The hedges were just coming into life – explosions of clustered white Blackthorn flowers, yellow willow catkins smothered in honeybees and the vivid fresh green of new leaves bursting from the buds of hawthorn, elder, spindle, hazel, oak and more. Birds flitted hither and thither – darting in and out of the living corridor – robins, wrens, chaffinches, chiff chaffs and others. Skylarks, in the adjacent fields, soared skywards singing as we walked past. Ian, ever sharp-eyed, spotted a lizard basking in the sunshine on a small patch of bare earth on the hedge-bank next to a clump of primroses. It darted away as we approached. Also basking on the hedge-bank was a tatty looking peacock butterfly – presumably one of last years’ having over-wintered.

The taller trees in the woodland had not yet broken into leaf allowing the ground flora to exploit the early season’s sunshine. The woodland floor was a green sea of leaves – linear, palmate, rounded, heart-shaped from which the season’s fresh flowers emerged – the delicate lilacs of the violets, cheery bright yellow celandines, white anemones, lemon primroses, purple ground ivy and the first beautiful bluebells. The air, pleasantly disturbed by the low hum of large Queen bumblebees flying just above the woodland floor – searching for pollen, nectar or perhaps nest sites. Occasionally we hear the shrill meeee -uu of a buzzard from way above, or the distant distinctive yaffle of a green woodpecker.

We stopped at our first box – empty. It was fastened onto a coppiced hazel stool beneath which was a myriad of small mammal pathways, visible as smooth earthy tracks interrupting the carpet of moss cloaking the area around the base of the tree. ‘Lunch for buzzards, kestrels and owls’ Ian always says.

Our second box – four tiny eggs laid neatly on a green nest of moss ‘Probably blue or great tit’ Ian mutters, ‘She’s still laying’.

Another couple of boxes – one of which has a possible winter dormouse nest – empty though. The ground around is disturbed and full of snuffle holes – left by badgers searching for worms, insects or tubers.

Another couple of boxes – one of which has a possible winter dormouse nest – empty though. The ground around is disturbed and full of snuffle holes – left by badgers searching for worms, insects or tubers.

Halfway through – a box with a clutch of bumblebee eggs enclosed in pollen and nestled in a mossy cushion. Nearby is a thimble-sized pot with a jagged rim – it is partially filled with nectar. The Queen bumblebee must be out collecting more. She will incubate her eggs with her body heat, rather like a bird, sustained in her endeavour by her pot of nectar.

Another box from which a blue tit, incubating her eggs, looks indignantly up at me. I quickly and gently replace the lid. The next box has slid down the tree and is just a few feet above the ground; it has lost its lid. A female blackbird keeps stock still, quietly watching us. She doesn’t quite fit– her tail protruding over the edge of the box. We leave her in peace, Ian making a note to replace the box in the winter.

Opening yet another box I find it full to the brim of brown oak and birch leaves. I gently part the leaves and see three wood mice, snuggled together. Again, I quietly replace the lid.

An unmistakable dormouse nest – long strands of honeysuckle bark interwoven into a loose ball with a smatter of other materials such as leaves and the odd bit of moss. Gentle investigation reveals a sleeping dormouse – eyes firmly closed and tail wrapped around body - female, 15g. She is torpid, the night temperature still dropping to zero or below; oblivious of our activity.

Eventually, having found yellow-necked mice, silk moth cocoons, spiders and a bank vole sheltering in a box we made our way out of the woodland via a wayleave. This was awash with early spring sunshine and it was a pleasure to see the first butterflies - brimstones, peacocks and orange-tips - flitting about. Many creatures use these rides – adders, slow worms and lizards bask in the sunshine; butterflies, bees, dragonflies, hoverflies and a host of other invertebrates feed on the nectar produced throughout the year in these sunny areas; birds and small mammals forage for seeds and invertebrates – in turn providing sustenance for birds of prey. Even secretive harvest mice have been found nesting in the lush, high vegetation that mimics unkempt fields.

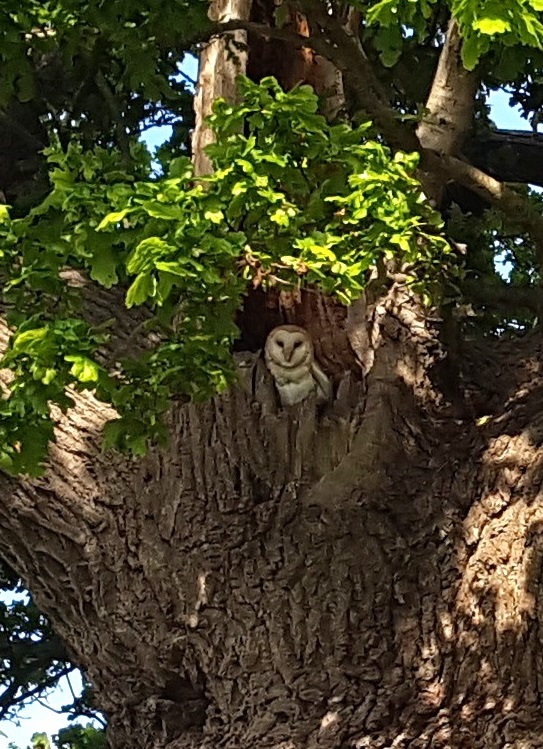

Then the night shift takes over. Bats galore! There is habitat for all bat species – those that hunt within these woodland rides or along the woodland edge; those that live in the woodland and hunt in the surrounding wetland; and bats living in surrounding villages in trees, attics, under roof tiles or other nooks and crannies, that commute to the Mid Arun Valley for the rich foraging grounds of woodlands and wetlands linked by a mosaic of wet ditches and hedgerows. The commuters use hedgerows and tree-lines as corridors, throughfares – hiding themselves in cryptic shadows reducing their visibility to the nocturnal predators – the owls.

Bats aren’t the only ones to commute in and out of this large block of woodland – toads live and hunt in damp places, such as the woodland floor, and commute to open ponds for the early spring breeding frenzy. Grass snakes move across landscapes from hibernation sites to foraging grounds and breeding sites – all may be in different locations with miles traversed to reach the best sites – the Binsted Rife Valley wetlands proving prime foraging habitat. We have also found dormice in boxes along the hedgerows linking the woodland to smaller copses. The hedge-banks are full of holes – inhabited by mammals such as voles, solitary bees and more.

Our different route back to the car takes us across a wet ditch – another type of corridor. The week before our dormouse box monitoring, we set up cameras in some of the ponds near the edge of the woods that are connected to the ditch network. Of course, we found water vole – why on earth wouldn’t we – everything else is in here in abundance!

Our different route back to the car takes us across a wet ditch – another type of corridor. The week before our dormouse box monitoring, we set up cameras in some of the ponds near the edge of the woods that are connected to the ditch network. Of course, we found water vole – why on earth wouldn’t we – everything else is in here in abundance!

We cross a sheltered field – rough grassland. Butterflies flit along the field edge, adjacent to the woodland, and two long-tailed tits are following. We spot a couple of goldfinches working their way across the field probing dead flower heads for seeds. This field, and several nearby areas, are identified as reptile hotspots by Highways England surveyors. The Grey Route will decimate these areas.

This landscape is teeming with life, a high proportion of which is on our endangered lists, under threat. The Grey route will result in this large woodland complex (largest on the coastal plain), comprising Binsted and Tortington Woods, becoming an ‘island’ surrounded by two major roads. Nesting birds will fall away – no longer able to hear each other’s calls, or predators approaching. Bats, badger, dormouse, reptiles, hedgehogs, newts, toads and more – will no longer be able to move across the landscape. The diversity of life present on Arundel’s doorstep will melt away.

Of course, Highways England, in their reports, state that the only creatures that will be killed once the road is up and running are the barn owls. This is utter nonsense! They are here and they would suffer, yes. But I have seen, badger, brown hare, hedgehogs, toads, newts, a blackbird and slow worm killed on the local smaller roads; let alone a major carriageway. Additionally, the literature says that bats are routinely killed on busy roads, but the bodies are not often seen because, like birds, they are hit rather than squished into the tarmac and being small, they are removed by scavengers fairly quickly.

Of course, Highways England, in their reports, state that the only creatures that will be killed once the road is up and running are the barn owls. This is utter nonsense! They are here and they would suffer, yes. But I have seen, badger, brown hare, hedgehogs, toads, newts, a blackbird and slow worm killed on the local smaller roads; let alone a major carriageway. Additionally, the literature says that bats are routinely killed on busy roads, but the bodies are not often seen because, like birds, they are hit rather than squished into the tarmac and being small, they are removed by scavengers fairly quickly.

Returning along the final hedgerow corridor, Ian bends and picks up a neat deposit of faecal matter, ‘hedgehog’ he mutters.

Dormouse surveys are carried out by fully licensed surveyors and we respectfully ask that you do not touch any boxes you see. Many thanks.